So, as I have explained in a previous introductory post, we went and did a special episode of our Italian-language fantasy cinema podcast, Chiodi Rossi, talking about stories instead of movies, and the stories of Clark Ashton Smith in particular.This to give to our followers some hopefully welcome reading suggestion for the summer, and also present the perspective of a writer and an editor on what are, by all means, classics of the imagination.

The set-up was the same we had tested in the Conan Re-Read – each one of us selected in this case three stories, we re-read them, and then discussed them.

For anyone interested and not fluent in Italian, I will now do a series of posts, summing up what we discussed – and I’ll start here with the first story my partner in crime, Germano, selected: The Beast of Averoigne.

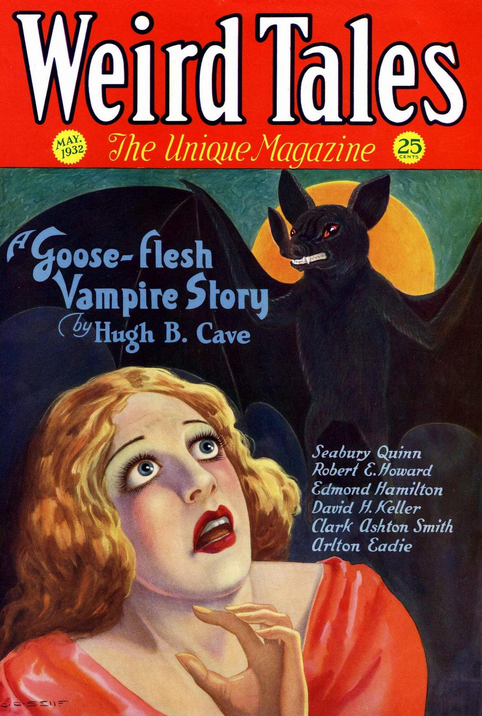

Originally pitched to and rejected by Weird Tales in 1932, The Beast of Averoigne was finally published by Farnsworth Wright in the May 1933 issue of Weird Tales.

The story belongs to the series CAS set in Averoigne, an imaginary chunk of Medieval France, and a venue for Gothic, macabre fantasies.

In a landscape bathed in the sanguine light of a mysterious comet, the good citizens and the monks of Perigon are plagued by a strange creature that kills by night – an alien monstrosity (when we’ll get to see it) that might remind some of the classic Thing from Another World. The events are presented as series of depositions of individuals involved in the action, and has almost a procedural structure; and if the final resolution is not so unexpected, we are not here for the shock reveal: we are here for the ride.

The plot might have been suggested to Smith by the reasl-life mystery of the Beast of the Gevaudan, a French cryptid that was the focus of the excellent film, Brotherhood of the Wolf.

One of the main topics we discussed in the podcast is how is it possible that CAS’s catalogue was never plundered by Hollywood – and the related mystery: how is it possible that in the last 100 years Smith has cyclically faded in and out of the fantasy readers’ consciousness, remaining the lesser known of the Three Musketeers of Weird Tales.

One possible reasons we have cooked up – more will pop up in the next posts – is that Smith was always more interested in creating worlds than in creating characters.

The Beast of Averoigne is a good example – no character is particularly memorable, and the story is a tour de force of imagination, landscape, mood and language.

It is Averoigne, that emerges as the true protagonist of the story – and when Smith came back to the setting, with different characters, it was Averoigne that remained center-stage. This might make filmic adaptation unappealing or overly complicated, and cause the fans to miss a charismatic character onto which to latch on.

The tale is suitably macabre and gruesome, and is a nice example of Smith’s baroque prose – the author being one that never expressed in less than a paragraph what could have been expressed in two words. And yet, right because of the language, CAS’ stories make for great read-out-loud experiences … and if you are interested, here is an audiobook version.

I have placed links to the original text and to the May 1933 issue of Weird Tales in the post.

Anyway, we have now begun – and we have five more stories to go.

Watch this space.