And here’s the last of the six stories we selected for our podcast about C.A. Smith and his works.

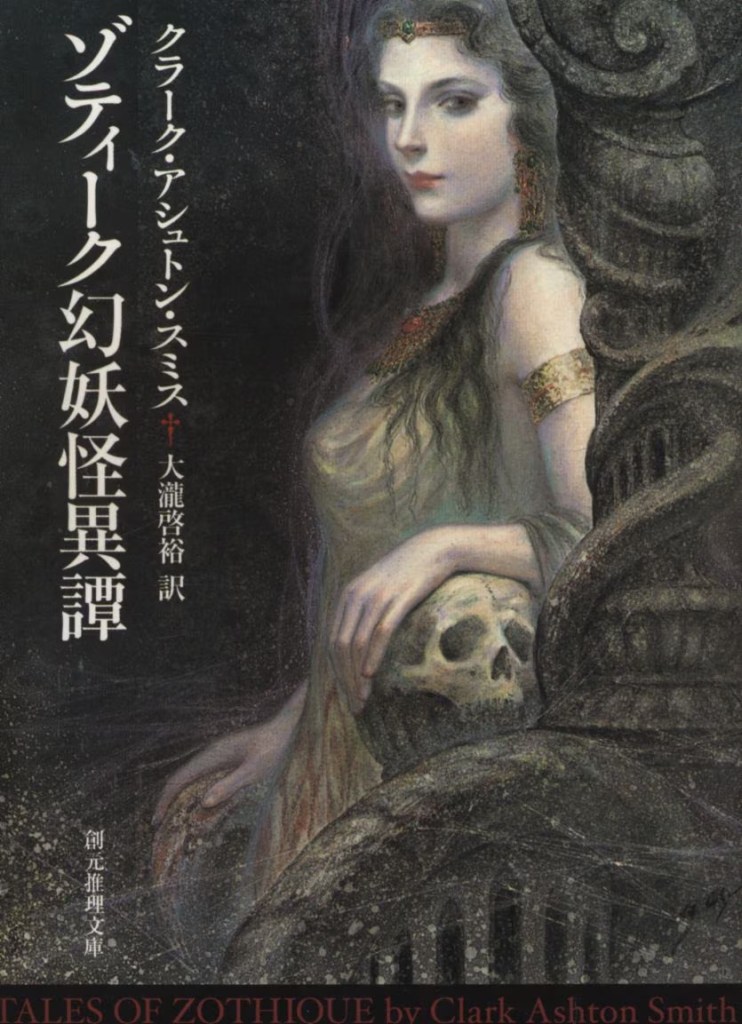

As already mentioned, for some reason – probably because he always wrote about worlds more than about characters – CAS was never as popular as R.E. Howard with the fantasy crowd, or H.P. Lovecraft with the horror people. CAS has been subject to cyclical disappearances and rediscoveries – a fitting destiny, considering the lost kingdoms ad forgotten peoples that often appear in his works.

Hopefully, our podcast (and this short series of posts) will lead someone to go and dig through the dusty stacks of the library, to learn more about Clark Ashton Smith.

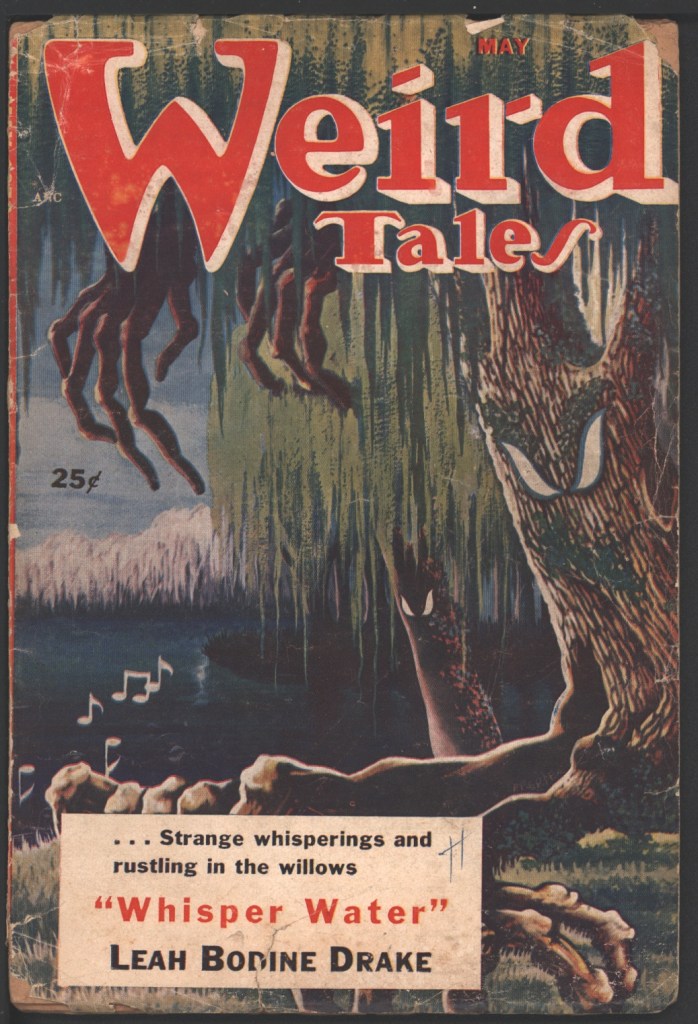

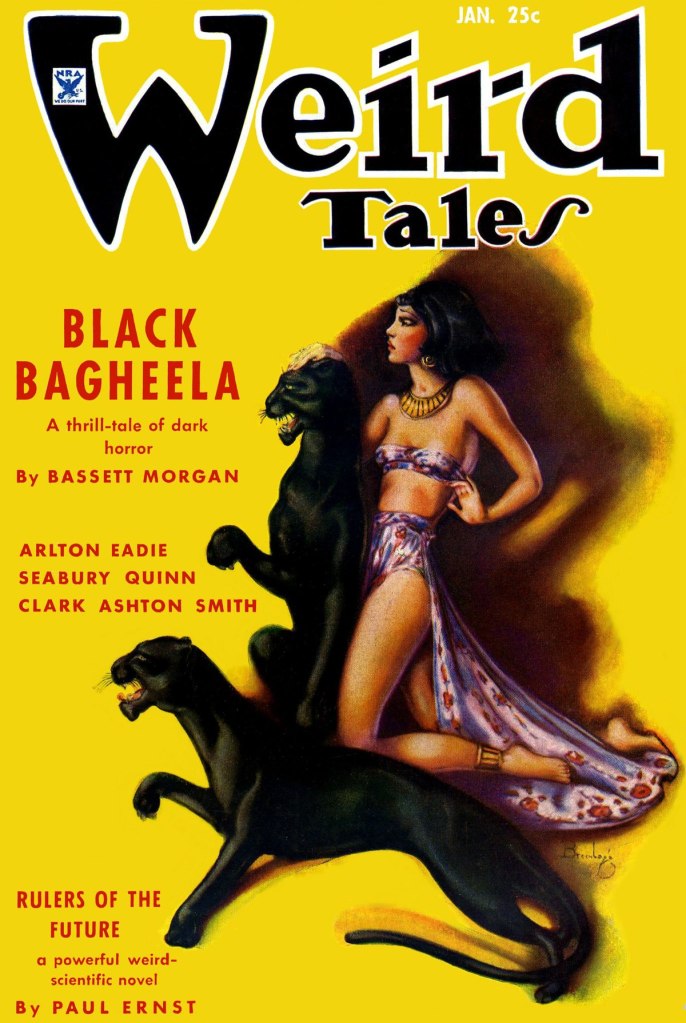

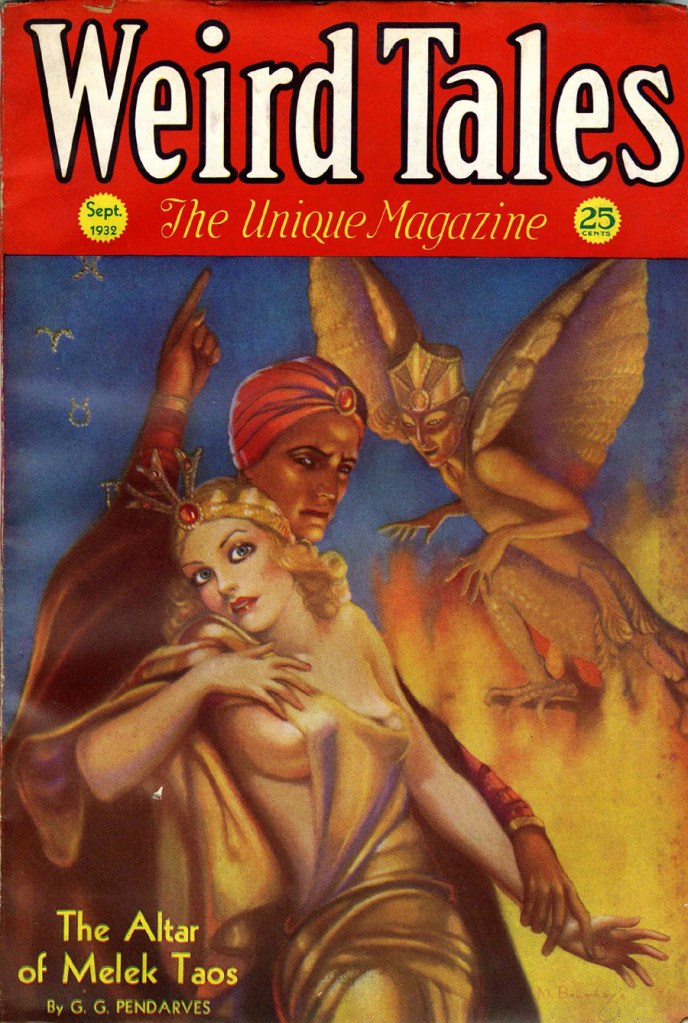

To end our brief exploration, I selected a late story belonging to the Zothique cycle – Morthylla, originally published in Weird Tales in May 1953.

Valzain, disciple of the poet Fomurza, has grown melancholic and unhappy, unable to participate in the revels in which Fomurza and his friends spend their time waiting for the Sun to die, and with the Sun, the Earth and Zothique, the last continent.

Seeking some sort of solace, Valzain visits an ancient graveyard, supposedly haunted by the lamia Morthylla – once a beautiful princess, now a creature of the night. Flirting with the lamia does revive the sagging spirits of the poet, but this surge of necrophiliac passion is destined to leave Valzain disappointed.

According to a certain tradition, CAS stopped writing after HPL’s death.

Morthylla shows it was not so straightforward – and it is a solid, very polished and elegant story, one that shows that CAS’ writing kept evolving in his later years.

The torrid atmosphere of decay and debauchery is quickly sketched, and then the action moves to the graveyard where Morthylla awaits. Or does she?

“Who are you?” he asked, with a curiosity that over powered his courtesy.

Clark Ashton Smith, Morthylla

“I am the lamia Morthylla,” she replied, in a voice that left behind it a faint and elusive vibration like that of some briefly sounded harp. “Beware me — for my kisses are forbidden to those who would remain numbered among the living.”

Valzain was startled by this answer that echoed his fantasies. Yet reason told him that the apparition was no spirit of the tombs but a living woman who knew the legend of Morthylla and wished to amuse herself by teasing him. And yet what woman would venture alone and at night to a place so desolate and eerie?

After the gruesome horrors of The Isle of the Torturers or the brutality of The Dark Eidolon, Morthylla is almost delicate in the way in which the main plot points are handled. This is one last spark of romanticism in a dying world soaked in hedonism and cynicism. And many of the objections that can be raised about the bulk of CAS’ work are meaningless here.

Morthylla is an almost perfect exercise in class and restraint, the dark undercurrents kept out of the way, but still perceivable at the edge of the story. This is Clark Ashton Smith at the top of his game. A perfect ending to our short overview.