We are still in Averoigne for the second story in our brief exploration of Clark Ashton Smith’s stories. This is not a scientific or literate investigation – we just picked three stories each, me and my friend Germano, three of the stories we like the best. The Colossus of Ylourgne is the second title on Germano’s hit list.

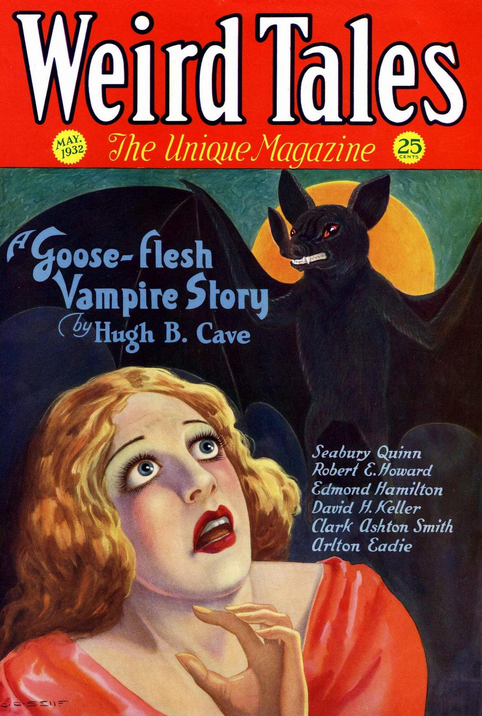

The story was published in the June 1934 issue of Weird Tales.

CAS’ story did not make the cover, that is a Margaret Brundage affair for Jack Williamson’s Wizard’s Isle.

We are back in Averoigne, and back to some darkly supernatural shenanigans. A revenge story, about Nathaire, a master of the dark arts that takes residence in an abandoned castle, and sets in motion a horde of the undead. As the main characters (and the readers) will discover, the plan of the necromancer is to use the reanimated bodies of the dead to create a colossus, a giant creature that will bring horror and destruction to the whole region.

When the monks of a nearby monastery fail in bringing back the natural order, it is up to alchemist Gaspard du Nord to take care of the menace.

Just as the previous Averoigne story we’ve seen, The Colossus of Ylourgne is built almost as a procedural, the narrative split in chapters each relating the events in a very chronicle-like style. The language is as usual baroque and peppered with unusual, antique terms. There is action, and horror – and CAS’ taste for the macabre is more evident in this second entry: the descriptions of the shambling army of the dead, and of the necromancer’s gruesome experiments are vivid and grotesque, and are really what makes this story memorable.

So memorable, in fact, that we can find many connections with other media.

Germano noted a similarity between the titular colossus and the giants in the manga and anime series Attack on Titan, and the scenes in Nathaire’s laboratory, where dead bodies are cooked and assembled into a giant war machine, might remind some readers of the kitchens in Thulsa Doom’s temple/fortress, in John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian.

They stood on the threshold of a colossal chamber, which seemed to have been made by the tearing down of upper floors and inner partitions adjacent to the castle hall, itself a room of huge extent. The chamber seemed to recede through interminable shadow, shafted with sunlight falling through the rents of ruin: sunlight that was powerless to dissipate the infernal gloom and mystery.

C.A. Smith, The Colossus of Ylourgne

The monks averred later that they saw many people moving about the place, together with sundry demons, some of whom were shadowy and gigantic, and others barely to be distinguished from the men. These people, as well as their familiars, were occupied with the tending of reverberatory furnaces and immense pear-shaped and gourd-shaped vessels such as were used in alchemy. Some, also, were stooping above great fuming cauldrons, like sorcerers, busy with the brewing of terrible drugs. Against the opposite wall, there were two enormous vats, built of stone and mortar, whose circular sides rose higher than a man’s head, so that Bernard and Stephane were unable to determine their contents. One of the vats gave forth a whitish glimmering; the other, a ruddy luminosity.

Near the vats, and somewhat between them, there stood a sort of low couch or litter, made of luxurious, weirdly figured fabrics such as the Saracens weave. On this the monks discerned a dwarfish being, pale and wizened, with eyes of chill flame that shone like evil beryls through the dusk. The dwarf, who had all the air of a feeble moribund, was supervising the toils of the men and their familiars.

The dazed eyes of the brothers began to comprehend other details. They saw that several corpses, among which they recognized that of Theophile, were lying on the middle floor, together with a heap of human bones that had been wrenched asunder at the joints, and great lumps of flesh piled like the carvings of butchers. One of the men was lifting the bones and dropping them into a cauldron beneath which there glowed a rubycoloured fire; and another was flinging the lumps of flesh into a tub filled with some hueless liquid that gave forth an evil hissing as of a thousand serpents.

Others had stripped the grave-clothes from one of the cadavers, and were starting to assail it with long knives. Others still were mounting rude flights of stone stairs along the walls of the immense vats, carrying vessels filled with semi-liquescent matters which they emptied over the high rims.

But certainly the most obvious media connection is with Dungeons & Dragons, and the classic Castle Amber module published for the first time in 1981. The Colossus graces the cover of this seminal D&D supplement, the work of legendary artist Errol Otus.

The story is different – and probably better – when compared to The Beast of Averoigne.

Not only we get more action and more horror, but we also get a proper leading man.

Gaspard du Nord is all that CAS is willing to give us in terms of a traditional main character and hero.

A man of occult knowledge and unparalleled courage in the face of horror, Gaspard could have become a recurring hero in his own cycle of adventures – but this was not to be, as CAS used him only in this story.

Another element that is more evident here than in the previous story is Smith’s macabre sense of humor – once defeated, the Colossus remains as a tourist attraction of sorts, and heroic Gaspard, despite being a student of the necromantic arts, becomes a darling of the Medieval church.

Smith’s passion for strange names gives us Nathaire and Ylourgne (and no, we do not know how that’s pronounced), and this long story is once again excellent when read out loud.

And therefore, for those who do not like the plain text version from The Eldritch Dark website, or the original Wird Tales I linked above, here’s the audiobook of the story.

Enjoy.

Ah, so that’s how it’s pronounced!