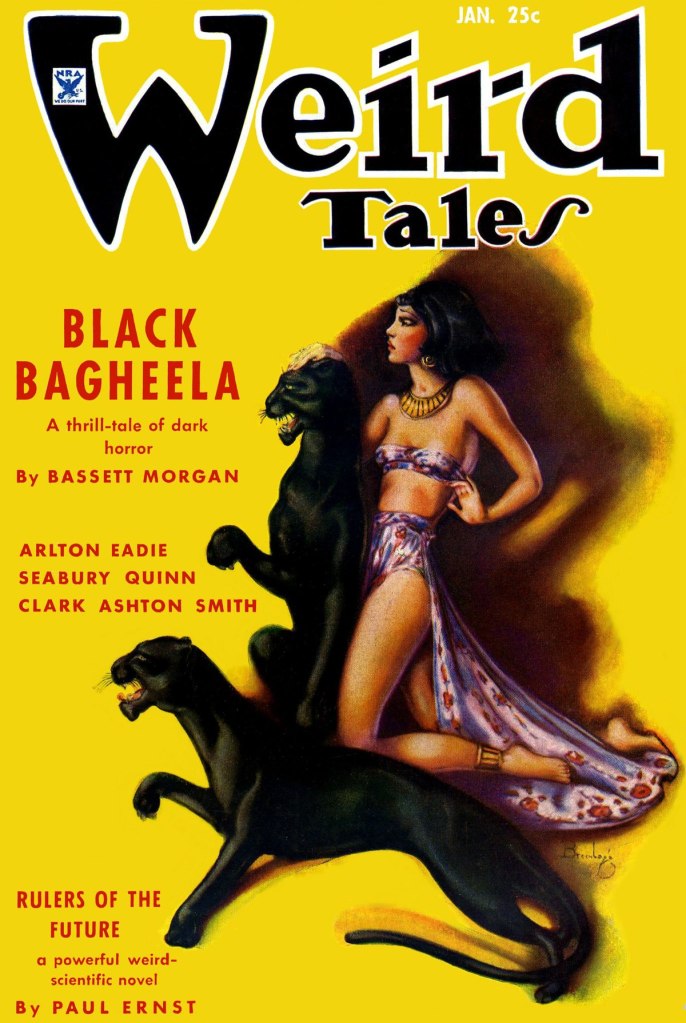

Fourth of the six Clark Ashton Smith stories we decided to do in our podcast, and the third choice from my friend Germano, The Dark Eidolon is another Zothique tale – because as mentioned before, Zothique is probably the best and most consistent of CAS’ story cycles. The story was originally published in the January 1935 issue of Weird Tales (an issue sporting one of WT’s most iconic covers ever).

The Dark Eidolon is particularly interesting (among other things) as it explicitly sets up a Clark Ashton Smith Continuum – the different settings of his stories are actually different ages of our world. The opening also introduces us to the basics of Zothique., explaining how in its final years Earth has regressed to a fantastical, magical state, peopled with demons and strange supernatural creatures and occurrences.

On Zothique, the last continent on Earth, the sun no longer shone with the whiteness of its prime, but was dim and tarnished as if with a vapor of blood. New stars without number had declared themselves in the heavens, and the shadows of the infinite had fallen closer. And out of the shadows, the older gods had returned to man: the gods forgotten since Hyperborea, since Mu and Poseidonis, bearing other names but the same attributes. And the elder demons had also returned, battening on the fumes of evil sacrifice, and fostering again the primordial sorceries.

Clark Ashton Smith, The Dark Eidolon

The story is rather long, and the plot suitably convoluted – just as in The Colossus of Ylourgne, we are dealing with the revenge of a necromancer, with a mysterious palace, and a colossal artifact. But the tone and the structure are different – and while the Averoigne story is presented as a collection of episodes, almost as a collection of legends, rumors and witness accounts, the Zothique story has a more straightforward narration, somewhat following the modes of an Oriental fantasy.

Namirrah is apowerful sorcerer, a servant of the demon lord Thasaidon (that apparently is pronounced very closely to “The Satan”), but in his youth he was a beggar and he was trampled by the horse on which prince Zotulla rode. He is not letting Zotulla go unpunished, despite his demon-master’s different opinion. Because, once grown up, Zotulla is the sort of decadent, debauched, corrupt ruler that actually does a lot of work for a demon like Thasaidon.

But Namirrah will not relent.

He builds a magical palace by the side of king Zotulla’s palace, and has the surrounding city trampled and destroyed by invisible demon horses. And then he invites Zotulla over, and will not take no for an answer.

In the end, Namirrah’s gruesome revenge comes to fruition, but Thasaidon, a master that will not be denied, has the last word in the whole affair.

Once again, the story is built on a succession of vivid, unexpected images, and hits the reader with a sensory (and linguistic) overload. The humor displayed by CAS in many of his stories is here much more subdued and macabre, and the finale is decidedly no laughing matter.

In the decadent, doomed venue of Zothique Smith has found his ideal setting for stories in which there seem to be no good guys. The world is doomed, the sun is going to die and take what’s left of humanity with itself, and nobody seems to have any plan, dream or aspiration, but have as much pleasure as possible.

And, in some cases, set old scores before it’s too late.

Some find Smith’s style, that is heavy on the telling and light on the showing, hard to swallow.

According to the rules somebody decided should be applied to all narrative, Smith’s stories should not work. We should reject them. They are not “cinematic”, they are not “hyper-kinetic”, they are not “immersive”.

Only they are, and work perfectly at immersing the reader in an opium dream of strangeness, horror and hard-to-forget legends.

And in case you’d rather listen to the story than read it, here you are…